NEW ENTRY

Setsubun at Home in Real Life: Store-Bought Beans, Messy Floors, and Dad as the Oni

Setsubun looks simple on paper: throw beans to chase away oni, then eat an ehōmaki sushi roll facing the lucky direction. But the real fun of Setsubun is how “un-serious” it becomes the moment you actually do it at home. Someone has to be the oni. Beans go everywhere. And that “silent, one-go” sushi rule turns into a family challenge that almost nobody follows perfectly. If you want the basic cultural meaning first, start here: What Is Setsubun? The Day Japan Throws Beans and Eats a Giant Sushi Roll Setsubun in Real Life: What It Actually Feels Like In modern Japan, Setsubun is usually a quick home event. Not a solemn ritual. Not a perfect performance. More like a yearly “reset” that turns into a small comedy scene—especially if there are kids in the house. Step 1: Most People Don’t Roast Beans at Home Traditional explanations often talk about roasted soybeans and why they should be roasted. But in real life, most households simply buy Setsubun beans. Stores sell ready-to-use packs of roasted soybeans, and many are marketed specifically for Setsubun. Roasting soybeans at home exists, but it feels like a minority choice now. For many people, the modern Setsubun starter kit is basically: a bag of roasted soybeans (fukumame) an oni mask (optional but fun) an ehōmaki roll (or two) Step 2: Someone Becomes the Oni This is where Setsubun turns into a “scene.” Someone puts on an oni mask. Someone else throws beans. If you’ve seen Setsubun photos online, you ...

What Is Setsubun? The Day Japan Throws Beans and Eats a Giant Sushi Roll

Setsubun is a Japanese seasonal tradition that marks the “turn of the season” in late winter, usually on February 3 (sometimes February 2). Families do simple rituals at home—throwing roasted soybeans and eating a lucky-direction sushi roll—to symbolically sweep out misfortune and welcome good luck. In modern Japan, Setsubun is less about religion and more about a yearly “reset”: a fun, family-centered moment that combines food, actions, and sometimes decorations into one memorable night. And honestly, you could sum it up like this: Setsubun is the day Japan throws beans… and then takes a big bite of a giant sushi roll. It sounds ridiculous at first. Beans? A whole sushi roll? Facing one direction? But once you understand what “oni” represents, why beans are roasted, and what the lucky direction means, it becomes a very Japanese way of handling winter: Push bad luck out. Pull good luck in. What Is Setsubun and When Does It Happen? Setsubun is Japan’s traditional “seasonal boundary” day. In modern Japan, it usually refers to the boundary between winter and spring, celebrated in early February. Most years it falls on February 3, but in some years it shifts to February 2 because it follows seasonal/calendar calculations rather than a fixed date. The Two Main Stars of Setsubun If you’re trying to understand Setsubun as living culture, focus on the two things most people associate with it today: Mamemaki: throwing roasted soybeans Ehōmaki: eating a thick sushi roll facing the lucky direction Everything else—masks, festivals, regional variations—makes more sense ...

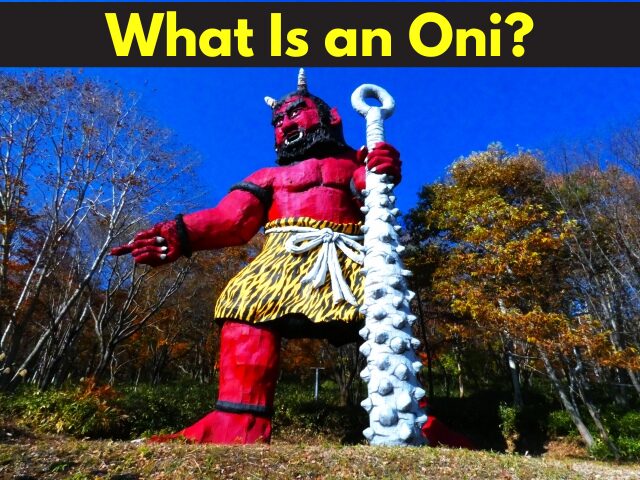

What Is an Oni? The Meaning Behind Japan’s Most Feared Folk Figure

Oni are symbolic beings in Japanese folk belief that give a human-like form to invisible threats—illness, disaster, fear, and spiritual impurity—so people can recognize them and deal with them through ritual, stories, and everyday life. This article explains what an oni is (beyond “demon”), why oni have a recognizable appearance, and how their symbols—like the iron club and tiger-skin pants—connect to language, festivals, and even protective uses in modern Japan. Quick Summary: Oni are not just “evil monsters.” They are cultural symbols that make unseen danger visible, so it can be named, acted out, and driven away—especially through rituals like Setsubun. Their iconic features (horns, wild hair, iron club, tiger-skin pants, and even color symbolism) reflect different kinds of fear and inner human weakness, which is why oni still appear in Japanese sayings, children’s songs, and protective motifs today. What Is an Oni? Oni are symbolic beings that give form to invisible threats—illness, disaster, fear, and spiritual impurity—so they can be recognized, named, and dealt with. In Japanese folk belief, oni are not simply “evil monsters.” They represent forces humans struggle to control: sudden disease, destructive impulses, social chaos, and inner weakness. By giving these abstract dangers a body and a personality, people could confront them through rituals, stories, and everyday language. An oni is not an enemy to defeat once and for all. It is a problem that must be acknowledged, faced, and managed—again and again. Why Fear Was Given a Face You cannot chase away misfortune if it has no shape. You ...

Why Garbage Disposal in Japan Works as a Social System

Garbage disposal in Japan works not simply because of strict rules, but because it functions as a shared social system. Japan’s famously clean streets are not maintained by constant enforcement or punishment. Instead, they are supported by an everyday system that quietly coordinates individual behavior, community trust, and urban life. This article explains why garbage disposal in Japan works as a social system—and why it can feel so difficult for outsiders to understand. Garbage Disposal as Invisible Infrastructure In many countries, garbage is treated as a purely personal matter. You throw it away, and the system handles the rest. In Japan, garbage disposal works differently. Trash is not just something to be removed—it is something that must be processed smoothly within a shared living environment. The garbage system is designed to keep neighborhoods quiet, clean, and predictable. Collection points, schedules, and sorting rules function as invisible infrastructure that supports daily life without drawing attention to itself. When garbage is disposed of incorrectly, it may simply be left uncollected. This is not meant as punishment, but as feedback: the system cannot absorb the waste in its current form. Why Sorting Is So Detailed Japanese garbage separation rules often appear excessive to newcomers. Burnable, non-burnable, plastics, recyclables, and oversized waste are separated with careful precision. This level of detail is not driven by moral pressure. It reflects how waste is processed downstream. Incineration facilities, recycling plants, and collection logistics are designed with specific inputs in mind. Sorting at the household level reduces friction later in ...

Why Japanese People Eat Sekihan: Red Rice as a Symbol of Celebration

Sekihan is a traditional Japanese dish known as “red rice,” eaten not as everyday food but to mark meaningful moments in life. In Japan, sekihan symbolizes celebration, growth, and renewal, expressing joy and gratitude quietly through food rather than words. This article explains what sekihan is, why its red color matters, and how it functions as a cultural signal for life’s milestones in Japanese everyday culture. Quick Summary: Sekihan is a traditional Japanese “red rice” eaten not as everyday food, but as a quiet way to mark life’s meaningful moments. Made with glutinous rice and azuki beans, its soft red color symbolizes protection, joy, and renewal. Rather than celebrating loudly, sekihan communicates good wishes through shared food—used for births, milestones, achievements, and even gentle returns to everyday life after change. What Is Sekihan, Simply Explained? Sekihan literally means “red rice,” but it is best understood as a cultural message rather than a recipe. It is made by steaming glutinous rice (mochi-gome) with azuki beans. As the beans cook, they release a gentle reddish tint that colors the rice. The rice itself is not “red rice.” Sekihan is not made from a special red variety of rice, and it is not artificially dyed. The color is simply the natural pigment from azuki beans. One more important detail: sekihan is typically steamed, not boiled. Steaming helps the grains stay chewy and lightly sticky—an “occasion texture” in Japan rather than an everyday one. What Does Sekihan Taste Like? Despite its cultural importance, sekihan itself is very ...