Quick Summary: Oni are not just “evil monsters.”

They are cultural symbols that make unseen danger visible, so it can be named, acted out, and driven away—especially through rituals like Setsubun.

Their iconic features (horns, wild hair, iron club, tiger-skin pants, and even color symbolism) reflect different kinds of fear and inner human weakness, which is why oni still appear in Japanese sayings, children’s songs, and protective motifs today.

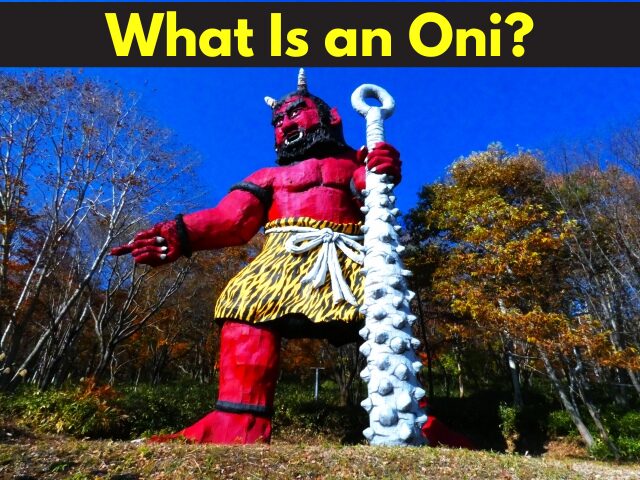

What Is an Oni?

In Japanese folk belief, oni are sometimes placed near shrines—not only as threats to drive away, but as symbolic figures connected to protection and reflection.

Oni are symbolic beings that give form to invisible threats—illness, disaster, fear, and spiritual impurity—so they can be recognized, named, and dealt with.

In Japanese folk belief, oni are not simply “evil monsters.” They represent forces humans struggle to control: sudden disease, destructive impulses, social chaos, and inner weakness.

By giving these abstract dangers a body and a personality, people could confront them through rituals, stories, and everyday language.

An oni is not an enemy to defeat once and for all. It is a problem that must be acknowledged, faced, and managed—again and again.

Why Fear Was Given a Face

Oni often appear in simplified, friendly forms—especially in children’s culture—showing how fear can be softened and made approachable.

You cannot chase away misfortune if it has no shape. You cannot throw beans at anxiety or illness.

By turning fear into a visible figure, Japanese culture made the invisible actionable. Once fear had a face, it could be named, played, scolded, laughed at, and symbolically expelled.

This is why oni appear so clearly in seasonal rituals like Setsubun. The act of throwing beans only works because the threat has been given a form.

What an Oni Looks Like

The iron club and tiger-skin pants are iconic symbols of oni, representing overwhelming force and untamed instinct rather than moral evil.

Oni share a recognizable appearance across centuries.

Horns mark them as beings outside human society. Wild hair suggests chaos and lack of control. Fangs and claws emphasize overwhelming force rather than calculated cruelty.

Oni are also commonly depicted as large, muscular figures with superhuman strength (kairyoku).

These exaggerated bodies are not meant to be realistic. They are visual shorthand for power that humans cannot resist—like disasters, illness, or destructive emotions that do not compromise.

Why Oni Carry an Iron Club

The kanabō is not just a weapon but a symbol of overwhelming, unavoidable force—so closely tied to oni that the image survives in everyday Japanese expressions.

When people picture an oni, most already imagine one thing: a massive figure holding an iron club.

The kanabō is not just a weapon that oni happen to carry.

It functions as a visual shorthand for what an oni represents.

The iron club symbolizes overwhelming, unfair force—power that cannot be negotiated with or reasoned away. It is heavy, blunt, and direct, much like sudden disasters, illness, or destructive impulses.

This deep association survives in everyday language.

Oni ni kanabō (“Giving an iron club to an oni”) is used today to describe a situation where someone already strong gains an additional advantage—like a skilled worker given perfect tools, or a powerful organization receiving even more resources.

The expression works because an oni is imagined as formidable before the club is added.

Why Oni Wear Tiger-Skin Pants

Tiger-skin pants are one of the most recognizable features of oni, symbolizing wildness and instinct—and later becoming a playful motif in children’s culture.

Immediately after the iron club, another feature stands out: the tiger-skin pants.

Oni are almost always depicted wearing a tiger-patterned loincloth, often referred to as tora no kawa no pantsu. This image is so familiar that it appears even in children’s songs and costumes.

The symbolism is layered: tigers represent ferocity and raw power, while animal skin suggests wildness and life outside human society.

Together, the tiger-skin pants mark the oni as a being ruled by instinct rather than social rules.

Notably, the pants are not armor. They do not protect the oni. Instead, they communicate something more unsettling: an oni does not need protection.

Oni Come in Different Colors

Different colored oni symbolize different kinds of fear and inner weakness, showing how Japanese folk belief classified emotions rather than treating oni as a single evil being.

In Japanese folk belief, oni are not all the same.

They are often described as appearing in different colors, each representing a particular kind of inner weakness, destructive emotion, or human flaw.

What is less widely known—even among Japanese people—is that each color of oni is also associated with a different weapon.

This system suggests that oni were not just imagined as external monsters, but as symbolic mirrors of human behavior. During rituals like Setsubun, driving these oni away was understood as a way to reflect on and correct one’s own inner state.

Red Oni

Red oni represent craving, desire, and greed—strong urges that can easily overwhelm reason.

They are often associated with intense emotion and sudden outbursts.

Weapon: Iron club

Blue Oni

Blue oni symbolize anger, resentment, and hostility—emotions that build quietly and corrode relationships over time.

They reflect fear that is cold and persistent rather than explosive.

Weapon: Forked pole (sasumata)

Yellow Oni

Yellow oni (sometimes described as white oni) represent restlessness, ego, and regret.

They are associated with an unsettled mind and the inability to make calm, fair judgments.

Weapon: Twin blades or saw

Green Oni

Green oni embody laziness, poor health, overindulgence, and lack of discipline.

Rather than sudden disaster, they reflect fears tied to everyday habits and physical decline.

Weapon: Naginata

Black Oni

Black oni symbolize doubt, complaints, and bitterness—states of mind that quietly erode peace and trust.

They represent fear that is internal and difficult to confront directly.

Weapon: Axe

Oni in Everyday Language

Oni are not confined to myths. The concept lives on in common expressions.

Oni no inuma ni sentaku

The expression oni no inuma ni sentaku compares strict authority to an oni, showing how the image of oni moved from myth into everyday language.

(“Doing laundry while the oni is away”) describes enjoying freedom while a strict authority figure is absent.

In modern terms, it can feel like relaxing—or doing things your own way—when a strict boss is out of the office.

Oni no me ni mo namida

(“Even an oni can shed tears”) reminds us that even someone seen as harsh or heartless can show compassion.

It quietly undermines the idea that oni are purely evil beings.

From Fear to Play

In children’s culture, oni often appear in cheerful and friendly forms, turning fear into something playful through songs like oni no pantsu.

Over time, oni shifted from terrifying symbols to playful figures.

Children sing about oni no pantsu, a cheerful song about an oni wearing tiger-striped underwear.

The song is intentionally silly. By turning a frightening figure into something humorous, fear is softened and made approachable—especially for children.

When Oni Become Protectors

Onigawara use the frightening image of an oni as protection, showing how fear itself can be repurposed to guard against harm.

Although oni are often portrayed as threats to be expelled, they are not always treated as enemies.

Sometimes, oni are turned into guardians.

A familiar example is oni-faced roof tiles used on temples and traditional buildings, where a fearsome face is meant to scare away misfortune.

And while it is not common, there are also shrines in Japan where oni are honored or associated with local protection.

Are Oni Evil?

Oni are not moral villains.

They represent problems that never disappear entirely: fear, desire, anger, and uncertainty. This is why oni return every year, every season, every generation.

In Japanese folk belief, fear is not something to destroy. It is something to recognize, manage, and live alongside.

That is what oni truly are.

FAQ

Are oni demons or devils?

Not exactly. Oni can look “demonic” in art, but in Japanese folk belief they function more as symbols that give shape to invisible threats like misfortune, illness, or destructive emotions. They are not a one-to-one match with the Western idea of the devil.

Why do oni have horns and wild hair?

Horns and unruly hair visually mark oni as beings outside human society—representing chaos, danger, and forces beyond rational control. The look is symbolic, not literal.

Why are oni so muscular and strong?

The exaggerated body is a shorthand for overwhelming power. Oni represent threats that humans cannot easily negotiate with—so they are drawn as huge, muscular figures with superhuman strength.

Why do oni carry an iron club?

The iron club (kanabō) symbolizes unfair, irresistible force. This image is so strong that it remains in modern language through the proverb oni ni kanabō, meaning “making someone already strong even stronger.”

What does the tiger-skin pants mean?

The tiger-skin loincloth signals wildness and ferocity. It suggests a being ruled by instinct rather than social rules—and it became such a familiar image that it appears in children’s songs and costumes.

Are oni always evil?

No. Oni can be expelled in rituals like Setsubun, but oni can also appear as protective figures—such as fearsome roof tiles meant to repel misfortune. Oni are better understood as symbols of forces to manage, not purely evil villains.

Why do oni come in different colors?

The different colors of oni are a symbolic way of classifying fear and human weakness.

Rather than representing separate species, each color highlights a particular inner problem—such as greed, anger, laziness, or doubt—that people have struggled with across generations.

By giving these weaknesses distinct colors (and even different weapons), Japanese folk belief made abstract emotions easier to recognize and reflect on.

In rituals like Setsubun, driving away colored oni was not only about expelling external evil. It also served as a reminder to look inward and confront one’s own destructive tendencies.

In this sense, color-coded oni function less like monsters and more like a moral and emotional map of human behavior.

Author’s Note:

As a Japanese person, I grew up seeing oni everywhere—at Setsubun, in sayings, and even in children’s songs—without always stopping to ask what they meant.

Writing about oni feels like translating a familiar “shape of fear” into words, and noticing how Japanese culture often turns fear into something we can face, laugh at, or even use for protection.