NEW ENTRY

Hinamatsuri (Girls’ Day) in Japan: Dolls, Food, and a Spring Wish for Growth

Hinamatsuri is a Japanese spring tradition held on March 3 that celebrates a girl’s healthy growth and future happiness. It is not a formal religious ceremony, but a family-centered seasonal custom practiced at home—often with hina dolls, symbolic foods, and a quiet wish for the year ahead. This guide explains what Hinamatsuri is, what the dolls mean, what people eat, and how the tradition is simplified in modern life. What Is Hinamatsuri? Hinamatsuri is a seasonal custom in Japan that marks early spring and expresses wishes for a girl’s health, safety, and future happiness. Rather than being a shrine ritual or a formal rite of passage, it works as a domestic celebration of growth: families acknowledge that a child is growing, time is moving forward, and a new season has arrived. It is sometimes translated as “Girls’ Day,” but the Japanese meaning is more symbolic than literal. It is not a birthday, and not every household celebrates it in the same way. The Meaning Behind the Hina Dolls Dolls as Symbols of Protection The most recognizable feature of Hinamatsuri is the display of hina dolls—typically an emperor and empress dressed in traditional court clothing. Historically, these dolls were connected to the idea of purification: misfortune could be symbolically transferred away from a child. Over time, this evolved into decorative dolls that quietly represent protection and well-being. Today, hina dolls are not treated as sacred objects, but as symbolic guardians placed in the home during the season. Traditional Displays vs Modern Homes In the past, ...

Japanese Valentine’s Day: Why Japan Celebrates Valentine’s Day Differently

Japanese Valentine’s Day looks familiar at first—but it works very differently from Valentine’s Day in most other countries. On February 14 in Japan, women give chocolate to men. Not flowers. Not cards. And not usually as a couple’s celebration. Most Japanese people do not associate the day with religion or history. Few know who Saint Valentine was, and even fewer think of Valentine’s Day as a Christian holiday. In Japan, it is simply understood as “Valentine’s Day”—a yearly event shaped by chocolate, timing, and shared social expectations. Quick Summary: Japanese Valentine’s Day is a modern cultural custom where women often give chocolate to men on February 14. While it began as a commercial event, it survived because the timing fit Japan’s school calendar and because chocolate worked as a clear social signal—first as a confession tool for students, and later as a practical expression of gratitude and connection among adults. What Makes Japanese Valentine’s Day Different? In many Western countries, Valentine’s Day centers on couples, romance, and mutual exchange. In Japan, the structure is different. The main action is giving chocolate, and it often starts as a one-sided gesture from women. This alone makes Japanese Valentine’s Day feel unusual to many visitors. The difference is not only about who gives what, but also about when the day takes place—and how that timing fits Japanese life. A Custom, Not a Religious Holiday For most Japanese people, Valentine’s Day is not experienced as a religious event. Its Christian origin rarely appears in everyday conversation. The ...

Setsubun at Home in Real Life: Store-Bought Beans, Messy Floors, and Dad as the Oni

Setsubun looks simple on paper: throw beans to chase away oni, then eat an ehōmaki sushi roll facing the lucky direction. But the real fun of Setsubun is how “un-serious” it becomes the moment you actually do it at home. Someone has to be the oni. Beans go everywhere. And that “silent, one-go” sushi rule turns into a family challenge that almost nobody follows perfectly. If you want the basic cultural meaning first, start here: What Is Setsubun? The Day Japan Throws Beans and Eats a Giant Sushi Roll Setsubun in Real Life: What It Actually Feels Like In modern Japan, Setsubun is usually a quick home event. Not a solemn ritual. Not a perfect performance. More like a yearly “reset” that turns into a small comedy scene—especially if there are kids in the house. Step 1: Most People Don’t Roast Beans at Home Traditional explanations often talk about roasted soybeans and why they should be roasted. But in real life, most households simply buy Setsubun beans. Stores sell ready-to-use packs of roasted soybeans, and many are marketed specifically for Setsubun. Roasting soybeans at home exists, but it feels like a minority choice now. For many people, the modern Setsubun starter kit is basically: a bag of roasted soybeans (fukumame) an oni mask (optional but fun) an ehōmaki roll (or two) Step 2: Someone Becomes the Oni This is where Setsubun turns into a “scene.” Someone puts on an oni mask. Someone else throws beans. If you’ve seen Setsubun photos online, you ...

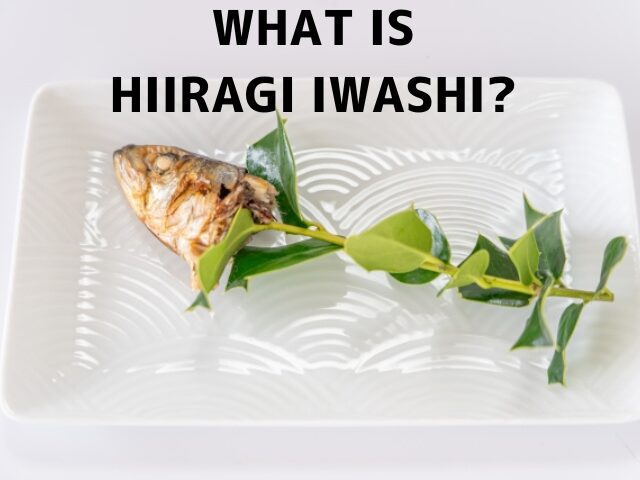

What Is Setsubun? The Day Japan Throws Beans and Eats a Giant Sushi Roll

Setsubun is a Japanese seasonal tradition that marks the “turn of the season” in late winter, usually on February 3 (sometimes February 2). Families do simple rituals at home—throwing roasted soybeans and eating a lucky-direction sushi roll—to symbolically sweep out misfortune and welcome good luck. In modern Japan, Setsubun is less about religion and more about a yearly “reset”: a fun, family-centered moment that combines food, actions, and sometimes decorations into one memorable night. And honestly, you could sum it up like this: Setsubun is the day Japan throws beans… and then takes a big bite of a giant sushi roll. It sounds ridiculous at first. Beans? A whole sushi roll? Facing one direction? But once you understand what “oni” represents, why beans are roasted, and what the lucky direction means, it becomes a very Japanese way of handling winter: Push bad luck out. Pull good luck in. What Is Setsubun and When Does It Happen? Setsubun is Japan’s traditional “seasonal boundary” day. In modern Japan, it usually refers to the boundary between winter and spring, celebrated in early February. Most years it falls on February 3, but in some years it shifts to February 2 because it follows seasonal/calendar calculations rather than a fixed date. The Two Main Stars of Setsubun If you’re trying to understand Setsubun as living culture, focus on the two things most people associate with it today: Mamemaki: throwing roasted soybeans Ehōmaki: eating a thick sushi roll facing the lucky direction Everything else—masks, festivals, regional variations—makes more sense ...

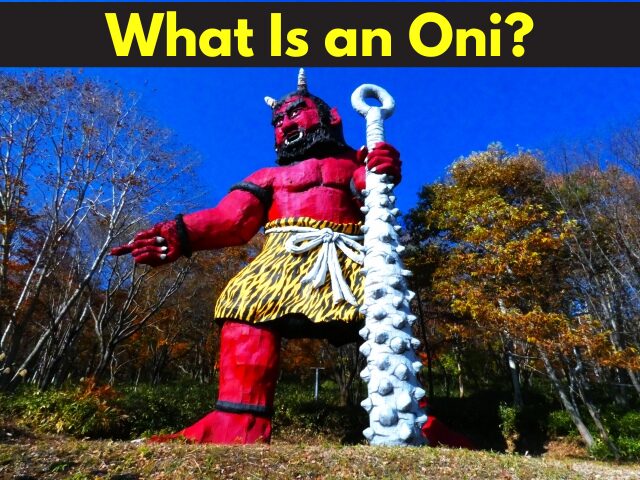

What Is an Oni? The Meaning Behind Japan’s Most Feared Folk Figure

Oni are symbolic beings in Japanese folk belief that give a human-like form to invisible threats—illness, disaster, fear, and spiritual impurity—so people can recognize them and deal with them through ritual, stories, and everyday life. This article explains what an oni is (beyond “demon”), why oni have a recognizable appearance, and how their symbols—like the iron club and tiger-skin pants—connect to language, festivals, and even protective uses in modern Japan. Quick Summary: Oni are not just “evil monsters.” They are cultural symbols that make unseen danger visible, so it can be named, acted out, and driven away—especially through rituals like Setsubun. Their iconic features (horns, wild hair, iron club, tiger-skin pants, and even color symbolism) reflect different kinds of fear and inner human weakness, which is why oni still appear in Japanese sayings, children’s songs, and protective motifs today. What Is an Oni? Oni are symbolic beings that give form to invisible threats—illness, disaster, fear, and spiritual impurity—so they can be recognized, named, and dealt with. In Japanese folk belief, oni are not simply “evil monsters.” They represent forces humans struggle to control: sudden disease, destructive impulses, social chaos, and inner weakness. By giving these abstract dangers a body and a personality, people could confront them through rituals, stories, and everyday language. An oni is not an enemy to defeat once and for all. It is a problem that must be acknowledged, faced, and managed—again and again. Why Fear Was Given a Face You cannot chase away misfortune if it has no shape. You ...