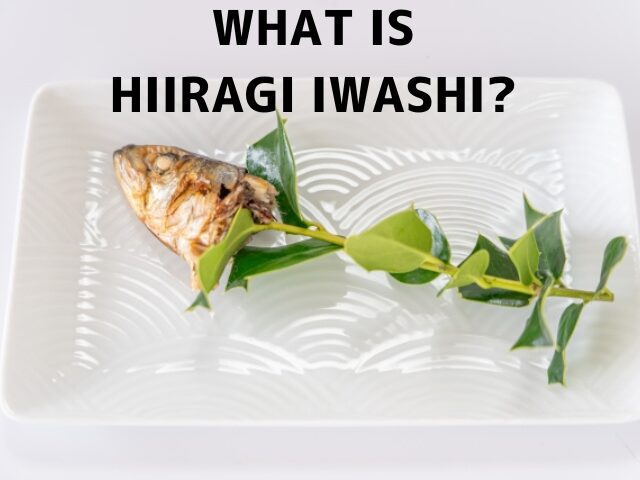

Hiiragi iwashi is a traditional Setsubun charm made from spiky holly leaves and a grilled sardine head.

In Japan, Setsubun marks a seasonal “reset” in early February.

And hiiragi iwashi is one of the most literal versions of that idea: a small, practical-looking object placed near the entrance to symbolically keep oni (misfortune) from entering the home.

Quick Summary: Hiiragi iwashi is a Setsubun charm made from spiky holly leaves and a grilled sardine head, placed outside (usually near the entrance) to symbolically keep oni—misfortune—out. It’s most associated with western Japan, and households vary on when to take it down and how to dispose of it.

If you’re new to Setsubun, start here: What Is Setsubun? You can also see the modern home version here: Setsubun in Real Life.

What Is Hiiragi Iwashi?

The sharp holly leaves and strong-smelling sardine head are meant to keep oni (misfortune) away.

Hiiragi iwashi is a Setsubun talisman made by combining hiiragi (holly leaves) and iwashi (a sardine), usually using only the grilled sardine head.

It is placed outside the home—most commonly at the front entrance—to ward off oni and bad luck.

Why Holly Leaves and a Sardine Head?

The logic is folk tradition, but it makes emotional sense the moment you see it.

- Holly leaves are sharp — the spiky edges are believed to repel oni.

- Grilled sardine smells strong — the odor (and smoke) is believed to drive oni away.

So hiiragi iwashi is not “pretty decoration.”

It is a small “keep-out” sign made from two things oni supposedly dislike: sharp leaves and a strong smell.

When Do People Put Up Hiiragi Iwashi?

Setsubun often bundles food and “protection” items—beans, ehomaki, an oni mask, and sometimes hiiragi iwashi.

Most households that do it put it up on Setsubun day.

It’s a quick, one-day seasonal custom for many people.

Where Do You Put It? (Not Inside)

Hiiragi iwashi is placed outside (often by the entrance), not indoors, to keep oni from entering.

Because the purpose is to stop oni from entering, hiiragi iwashi is placed outside, not indoors.

The most common spot is the front entrance.

People often attach it by:

- taping the holly stem to a surface, or

- tying it with string, or

- fixing it near the door area where it won’t fall easily.

How Hiiragi Iwashi Is Made (Home Version)

There are many variations, but the “everyday” version is usually simple.

Tip: Grill the sardine well. A common real-life reason is simple: if it’s undercooked, it can smell too fishy when you display it.

- Grill a sardine well (many people use a fish grill) so it doesn’t stay too raw-smelling.

- After it cools, cut off the head.

- Attach the holly sprig by pushing it through the head area (often from around the gills toward the eye).

It sounds dramatic when written out, but in real life it’s a quick seasonal DIY.

When Do You Take It Down?

There’s no single nationwide rule.

When to remove hiiragi iwashi depends on the region and the household.

Some take it down the next day.

Others leave it up for the rest of February.

And in some places, people keep it much longer—sometimes even until the next year.

Like many Setsubun customs, it’s more “local habit” than a strict rule.

How Do You Dispose of Hiiragi Iwashi?

Some people dispose of hiiragi iwashi by bringing it to a shrine for otakiage (ritual burning).

There are a few common approaches, and again, households vary.

- Shrine disposal: some people bring it to a shrine for ritual burning (often described as otakiage).

- At home: some burn it down to ash, or bury it in a garden.

- Simple home disposal: another method is to wrap it in clean white paper, sprinkle a little salt, and dispose of it respectfully.

Salt is often treated in Japan as a simple “purifying” element, so this is a very typical everyday-culture solution.

Do People Eat Sardines on Setsubun Too?

Hiiragi iwashi uses only the head—many households cook the rest of the sardine as food.

Yes—because hiiragi iwashi uses only the head, the rest of the sardine doesn’t have to go to waste.

In some areas (especially in parts of western Japan), eating sardines on Setsubun day is part of the seasonal food tradition.

And in real life, that usually means the “body” becomes a normal home-cooked dish.

Ginger-Simmered Sardines (Shōga-ni)

Shōga-ni is a classic choice. Ginger helps soften the fishiness, and it fits the winter Setsubun mood perfectly.

Tatsuta-age (Japanese-Style Fried Sardines)

Tatsuta-age is another easy option: lightly season the fish (often soy-based) and fry it for a crisp coating.

It’s a good example of how Setsubun often links protection and food in one event.

Is Hiiragi Iwashi Common Everywhere in Japan?

Not really.

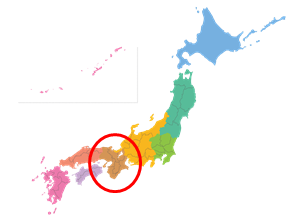

Hiiragi iwashi is often associated with western Japan (commonly linked with the Kansai area).

That said, variations exist, and some households in other regions also do it.

Like many Setsubun customs, it depends on the region—and the family.

FAQ

Is hiiragi iwashi a religious item?

For most people today, it’s a seasonal folk charm rather than a religious requirement. It’s often treated as everyday culture connected to Setsubun.

Do you put hiiragi iwashi inside the house?

No. It is placed outside, usually near the front entrance, because it is meant to stop oni (misfortune) from entering.

Why does it use a sardine head instead of the whole fish?

The charm traditionally uses the head, while the rest can be eaten. The “strong smell” idea is also strongest around the grilled fish head.

Does hiiragi iwashi smell bad?

It can smell fishy if it’s not grilled enough. Many people grill the sardine well to reduce raw odor before using the head for the charm.

Is hiiragi iwashi done everywhere in Japan?

No. It is often linked to western Japan (especially Kansai), though some households in other regions also do it as a local or family custom.

Final Thoughts

Hiiragi iwashi is one of the most “hands-on” Setsubun customs.

It’s small, sharp, and a little strange—exactly the kind of folk tradition that survives because it feels memorable.

And it shows something very Japanese about seasonal culture: even a simple entrance charm can combine symbolism, food, and everyday practicality in one object.

Author’s Note

In the area where I live, not many households put up hiiragi iwashi—but some definitely do.

Even as a Japanese person, I find it a slightly unusual custom, and I can’t help thinking, “Who came up with this?”

Japan has many traditions like this—small, mysterious habits that survive across generations, even when they look a little strange from the outside.