What Is Oshogatsu (Japanese New Year)?

In Japan, New Year’s celebrations, called Oshogatsu (お正月), are the most important annual event.

Unlike Western countries where December 31 is central, Japanese families focus on January 1–3, spending time with relatives, visiting shrines, and preparing symbolic food.

It is a time for starting fresh, showing gratitude, and praying for health, happiness, and prosperity in the year ahead.

Decorations for the New Year

Kadomatsu (門松)

Kadomatsu are bamboo and pine decorations placed at the entrance of homes or buildings.

The bamboo represents growth and strength, while pine symbolizes longevity and resilience.

They are meant to welcome ancestral spirits and the Shinto deities who bring blessings for the year.

Shimenawa (注連縄)

A sacred rope made of rice straw, shimenawa is hung on doors or gates to ward off evil spirits.

Paper streamers called shide are often attached, marking the space as pure and protected.

Kagami Mochi (鏡餅)

Kagami mochi is a decoration made of two stacked rice cakes with a small bitter orange (daidai) on top.

The round shape represents harmony, while the daidai symbolizes prosperity for future generations.

Families display kagami mochi in their living rooms as an offering to the gods and later eat it in a ritual called kagami biraki in January.

Food Traditions

Osechi Ryori (おせち料理)

Osechi ryori is a set of traditional dishes served in colorful lacquered boxes called jubako.

Each dish carries symbolic meaning:

Kuromame (black beans)

Good health and hard work.

Sweet black soybeans simmered slowly in sugar and soy sauce.

Soft, slightly sweet, and glossy in appearance.

Kazunoko (herring roe)

Fertility and prosperity.

Salted herring roe, known for its crunchy texture.

Often lightly seasoned with soy sauce and dashi.

Datemaki (sweet rolled omelet)

Academic success and knowledge.

A rolled omelet blended with fish paste, giving it a sweet flavor and fluffy texture.

Served in slices like a yellow spiral.

Originally, osechi was prepared in advance so families could avoid cooking during the first days of the year, a time reserved for rest and prayer.

Ozoni (お雑煮)

Ozoni is a soup containing rice cakes (mochi), vegetables, and sometimes chicken or fish.

Recipes vary by region: miso-based in western Japan, clear broth in eastern Japan.

Eating ozoni is believed to bring strength and good fortune for the coming year.

Visiting Shrines and Temples

Hatsumode (初詣)

Hatsumode is the first shrine or temple visit of the year.

Families pray for happiness, safety, and prosperity, and often purchase omamori (protective charms) or draw omikuji (fortune slips).

Popular spots like Meiji Jingu in Tokyo or Fushimi Inari in Kyoto attract millions of visitors during the first days of January.

Omikuji and Omamori

Drawing a fortune slip (omikuji) and buying protective charms (omamori) are common practices during hatsumode.

These customs help set the tone for the year, offering both blessings and guidance.

Games and Activities

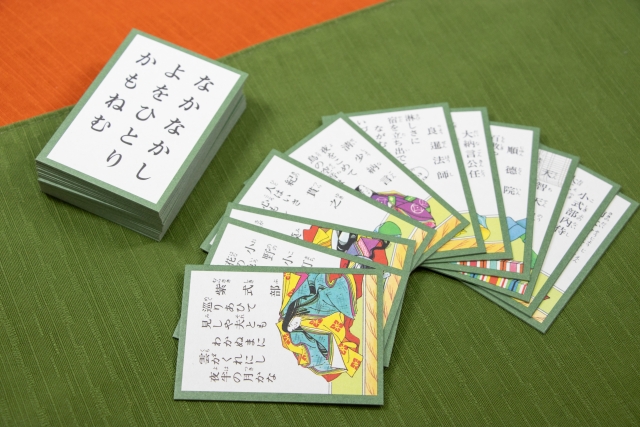

Karuta (かるた)

Karuta is a traditional card game played during the New Year.

One popular version, Hyakunin Isshu Karuta, involves classical Japanese poetry, making it both fun and educational.

Hanetsuki (羽根つき)

Similar to badminton, hanetsuki is played with a wooden paddle (hagoita) and a shuttlecock.

Traditionally, it was believed that playing hanetsuki protected against evil spirits.

Modern New Year Traditions

Today, Japanese New Year celebrations also include modern customs:

-

Watching the first sunrise of the year (hatsuhinode), symbolizing renewal.

-

Sending New Year’s greeting cards (nengajo) to friends, family, and colleagues.

-

Watching television specials, such as music countdowns and comedy shows, which have become part of the festive atmosphere.