Wasabi is more than a hot green paste served with sushi. In Japan, it exists in two very different forms—freshly grated hon-wasabi and convenient tube wasabi—and both play meaningful roles in everyday food culture.

This article explains what wasabi really is, why these two forms coexist, how they taste and feel different, and how Japanese people actually use them in daily life.

Quick Summary:

Wasabi is a Japanese plant whose sharpness comes from aroma rather than lingering heat. While real wasabi is rare and carefully handled, tube wasabi dominates everyday use.

Understanding why these two forms coexist reveals how Japanese food culture balances convenience and craftsmanship.

What Is Wasabi?

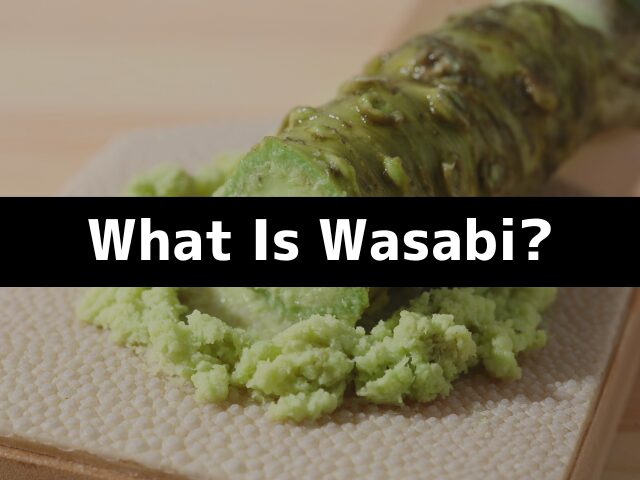

Real wasabi, known as hon-wasabi (Wasabia japonica), is a perennial plant native to Japan. It grows naturally along cool, clean mountain streams where water flows constantly and temperatures remain stable.

The part we eat is the rhizome. When freshly grated, enzymes activate compounds that create wasabi’s signature sensation: a sharp, aromatic heat that rises quickly through the nose and fades just as fast.

Unlike chili peppers, wasabi does not burn the tongue. Its impact is fleeting and clean—designed to sharpen flavors, not overpower them.

Why Wasabi Comes in Two Forms

If real wasabi exists, why is most “wasabi” a paste from a tube?

The answer is practical, not deceptive.

Traditional wasabi cultivation relies on clean, flowing mountain water.

Real wasabi is difficult to grow, slow to mature, and fragile after harvest. Cultivation requires pristine water, shade, and years of care. Once grated, its aroma peaks for only a short time.

Tube wasabi—typically made from horseradish, mustard, and coloring—solves these limitations.

It is affordable, shelf-stable, and always available.

Rather than replacing real wasabi, tube wasabi fills a different role. The two forms coexist because they serve different needs.

How Japanese People Actually Use Wasabi

In everyday life in Japan, tube wasabi is what most people reach for. It’s quick, familiar, and its sharp heat rushes straight through the nose—instant and unmistakable.

Freshly grated hon-wasabi, however, tells a different story. As you bring it closer, a green, almost leafy aroma rises first. The heat follows softly, spreading gently before disappearing, leaving behind a faint sweetness rather than pain.

One is not “better” than the other. They are used for different moments.

- Tube wasabi: daily meals, home cooking, convenience

- Fresh wasabi: special meals, craftsmanship, fleeting flavor

Taste and Sensory Differences

Freshly grated hon-wasabi releases aroma first, while tube wasabi delivers immediate sharp heat.

The difference between the two is not just strength, but character.

Aroma: Fresh wasabi releases a vivid green scent the moment it is grated. Tube wasabi’s aroma is muted and uniform.

Heat: Real wasabi’s heat rises quickly and fades within moments. Tube wasabi tends to linger longer and feel sharper.

Aftertaste: Fresh wasabi leaves a subtle sweetness. Tube wasabi often ends abruptly.

These differences explain why freshly grated wasabi is used sparingly and with care.

When Real Wasabi Matters

In traditional sushi restaurants, wasabi is treated as part of the craft.

Chefs grate it just before serving and place it directly on the fish, not mixed into soy sauce.

The goal is balance: enhancing aroma without masking the ingredient.

This is why real wasabi is often associated with restraint and timing. It is meant to be experienced in the moment, not stored or rushed.

Wasabi as Cultural Balance

In traditional sushi, wasabi is placed directly on the fish to preserve aroma.

Wasabi reflects a broader pattern in Japanese food culture: the coexistence of convenience and craftsmanship.

Everyday life favors efficiency. Special moments favor care.

Rather than choosing one over the other, Japanese cuisine allows both to exist—each respected for what it offers.

Conclusion

Wasabi is not simply a condiment, nor is it a test of authenticity. It is a tool for flavor, timing, and balance.

Understanding why real and tube wasabi coexist helps explain how Japanese food culture values both practicality and fleeting perfection.

The next time you encounter wasabi, the question may not be “Is this real?” but “What role is it meant to play?”

Frequently Asked Questions

Is most wasabi outside Japan fake?

Most wasabi served globally—and often even in Japan—is horseradish-based. This is normal and widely accepted for everyday use.

Why is real wasabi so expensive?

Real wasabi requires clean running water, stable temperatures, and years of growth. These conditions make production limited and costly.

Does tube wasabi contain any real wasabi?

Some premium products include a small percentage of real wasabi for aroma, but most are primarily horseradish-based.

Why does real wasabi taste milder?

Its heat is aromatic and short-lived rather than lingering. This makes it feel gentler despite being freshly prepared.

Should wasabi be mixed into soy sauce?

In everyday settings, mixing is common. In traditional sushi culture, wasabi is placed directly on the fish to preserve aroma.

Final Thoughts

There are two very different foods sold under the name wasabi.

Most people today enjoy the convenient version—and that’s perfectly fine. But understanding real wasabi reveals why this plant holds such cultural weight in Japan.

It is not about authenticity alone, but about choosing the right expression for the moment.

Author’s Note

In everyday life in Japan, tube wasabi is what most of us reach for. Its sharp heat cuts straight through the nose—quick and unmistakable.

But when you taste freshly grated hon-wasabi, the experience changes. The aroma arrives first, the heat follows gently, and it fades before turning into pain.

On YUNOMI, I try to translate that everyday realism—convenience versus craft—into cultural context that makes sense outside Japan.