Shojin-ryori is Japan’s traditional Buddhist cuisine, created for monks and based on non-violence, balance, and mindfulness. It avoids meat, fish, and pungent ingredients, using vegetables, tofu, and simple seasonings instead.

Many of its dishes quietly shaped everyday Japanese home cooking, so understanding shojin-ryori also reveals the roots of Japanese food culture.

What Is Shojin-Ryori?

Shojin-ryori is a plant-based Buddhist cuisine in Japan that focuses on purity, harmony, and appreciation for all life. It developed in Zen temples as the daily food of monks and is closely connected to spiritual practice rather than luxury or entertainment.

Its foundations include:

- Non-violence (not killing animals for food)

- Moderation and simplicity

- Purification of body and mind

- A “zero waste” philosophy when using ingredients

- Gratitude and humility toward all living things

Shojin-ryori is not simply “vegetarian food.” It is a way of cooking and eating that turns every meal into a reminder of respect for life.

Core Principles of Shojin-Ryori

Traditional shojin-ryori follows several important rules:

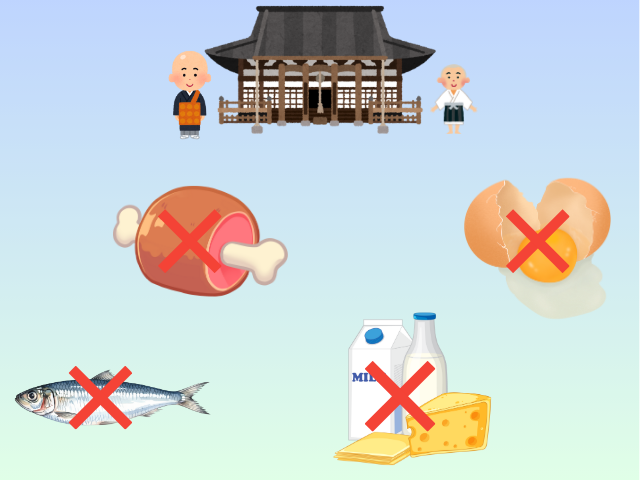

No Meat, Fish, or Animal Products

Animals are not killed for food, in line with Buddhist precepts against taking life. Classic shojin-ryori avoids meat, fish, and often eggs and dairy as well.

No Pungent Ingredients (the “Five Pungents”)

Garlic, onion, scallions, leeks, and chives are avoided. These strong-smelling vegetables are believed to stimulate the senses, making it harder to maintain a calm, meditative state.

The “Rule of Five”

To keep each meal balanced, shojin-ryori often uses:

- Five colors: green, yellow, red, black, and white

- Five flavors: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami

- Five methods: raw, simmered, grilled, fried, and steamed

This approach makes the meal visually beautiful, nutritionally varied, and mentally satisfying without relying on strong seasonings.

Nothing Goes to Waste

Peels, stems, and scraps of vegetables are not thrown away.

They are used for stocks, pickles, or side dishes. This “use everything” mindset is one of shojin-ryori’s most important contributions to Japanese cooking culture.

Representative Dishes of Shojin-Ryori

To understand shojin-ryori, it helps to look at some classic dishes that often appear in temple cuisine.

1. Goma-dofu (Sesame “Tofu”)

A silky, pudding-like block made from ground sesame and starch, not soybeans. It is rich, smooth, and often served with a little soy sauce or wasabi. It is one of the signature dishes of temple cuisine in places like Mount Koya.

2. Kenchinjiru (Vegetable and Tofu Soup)

A hearty soup made with root vegetables, tofu, and vegan dashi from kombu kelp and dried shiitake mushrooms. It is simple but deeply comforting and is now common in homes and school lunches as well.

3. Shiraae (Mashed Tofu Salad)

A salad of mashed tofu mixed with vegetables and seasoned with soy sauce and sesame. It is mild, nutritious, and appears both in temple cuisine and in everyday home meals.

4. Koya-dofu (Freeze-Dried Tofu)

Freeze-dried tofu with a spongy texture that absorbs flavor well. Originally a temple food, it is high in protein and calcium and is now often used in healthy home cooking and care facilities.

5. Vegetable Tempura

Seasonal vegetables coated in a light batter and fried. In shojin-ryori, the batter is made without egg and the stock used for dipping sauce is plant-based.

6. Nimono (Simmered Dishes)

Vegetables gently simmered in a light broth, usually made from kombu and soy sauce. This style of cooking is a core technique in both temple and home kitchens.

How Shojin-Ryori Shaped Everyday Japanese Home Cooking

Many people imagine shojin-ryori as something special that you only find at temples. In reality, its influence reaches far into ordinary Japanese homes.

Some typical connections include:

- Kenchinjiru: once a temple soup, now a familiar home dish and school lunch item.

- Shiraae: a classic side dish that follows shojin-ryori’s idea of using tofu and seasonal vegetables.

- Koya-dofu: originally a temple preservation food, now used in everyday cooking and often served in meals for older people because of its nutrition.

- Vegetable simmered dishes: many Japanese simmered dishes are built on a light, plant-based broth with gentle seasoning, reflecting shojin principles.

- The “one soup and three dishes” style: the idea of serving rice, soup, and three side dishes has roots in temple meal structure.

In this way, shojin-ryori is not just a special temple meal. It quietly forms the backbone of what many people think of as “ordinary” Japanese food.

Shojin-Ryori and Kaiseki Cuisine

Kaiseki, Japan’s refined multi-course cuisine, is often associated with tea ceremony and high-end dining. However, its roots are deeply connected to temple food.

Originally, kaiseki began as a simple meal served to accompany tea, influenced by the modest, balanced meals of Zen temples. Over time, fish, meat, and luxury ingredients were added, and presentation became more elaborate. But the foundations remained the same:

- Respect for seasonal ingredients

- Delicate flavors that never overpower

- Careful balance of color, shape, and texture

In this sense, shojin-ryori can be seen as the quiet ancestor of kaiseki — the spiritual and culinary foundation on which Japanese haute cuisine was built.

Shojin-Ryori and Modern Vegan / Vegetarian Food

Because shojin-ryori is plant-based, it is often compared to vegan cuisine and is popular among health-conscious visitors.

There are, however, some differences:

- Traditional shojin-ryori avoids strong-smelling vegetables like garlic and onion, while modern vegan cooking often uses them.

- Shojin-ryori is deeply connected to Buddhist practice and mindfulness, not just health or preference.

- The goal is to bring out the natural taste of ingredients with minimal seasoning, rather than to imitate meat dishes.

In many temples and restaurants today, shojin-style meals remain fully plant-based. However, some modern places may add dairy products or use egg in certain dishes for general customers. If you are strictly vegan, it is wise to confirm the ingredients in advance.

Where to Experience Shojin-Ryori in Japan

You can find shojin-ryori in several types of places:

- Temple lodgings (shukubō): especially in temple towns, where guests can stay overnight, join morning prayers, and eat traditional temple meals.

- Temples in cultural cities: some well-known temples in cities like Kyoto serve shojin-ryori by reservation.

- Specialty restaurants: major cities such as Tokyo and Osaka have restaurants offering shojin-inspired vegan or vegetarian menus.

These meals are not just about eating. They offer a chance to experience a slower rhythm of life and a more mindful way of relating to food.

FAQ

Is shojin-ryori always vegan?

Traditionally, yes. Classic shojin-ryori avoids meat, fish, eggs, and dairy. However, some modern temples and restaurants may include dairy or egg, so vegans should always ask in advance.

Why are garlic and onion avoided?

They are believed to stimulate the senses and increase desire, which can disturb meditation and inner calm. For this reason, many Buddhist cuisines avoid strong-smelling vegetables.

Is shojin-ryori bland?

No. While it is gently seasoned, it has plenty of umami from kombu, shiitake mushrooms, miso, soy sauce, and sesame. The goal is depth and balance, not strong or spicy flavors.

How is shojin-ryori different from ordinary Japanese home cooking?

Many techniques and dishes overlap, but shojin-ryori follows stricter rules about ingredients and waste. Home cooking may include meat, fish, and pungent vegetables, while still being influenced by the light seasoning and balance of temple cuisine.

Can anyone enjoy shojin-ryori, even if they are not Buddhist?

Yes. Shojin-ryori is open to everyone. Many people enjoy it as a cultural, spiritual, and culinary experience, regardless of their personal beliefs.

Conclusion

Shojin-ryori is more than just “temple food.” It is a way of cooking that reflects Buddhist ideas of non-violence, gratitude, and respect for nature. Its influence can be seen in everything from soups and simmered dishes to tofu traditions and the structure of Japanese meals.

By learning about shojin-ryori, you are not only discovering a type of Buddhist cuisine — you are also getting closer to the heart of Japanese food culture itself.