In Japan, it is common to see "no tattoos allowed" signs at establishments such as restaurants, public bathing areas (Onsen), gyms, public swimming pools.

But why is this?

Tattooing is the most misunderstood form of art in contemporary Japan.

Demonized by centuries of prohibitions and rarely discussed today in civilized circles, people with tattoos are outcasts in their own country — banned from many beaches, pools, and public baths.

Reason

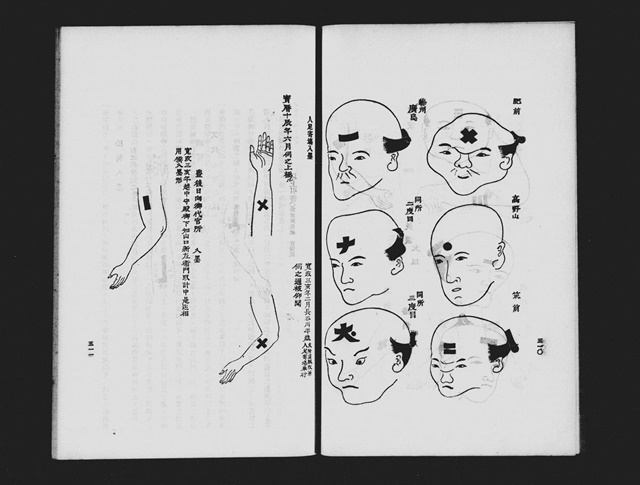

Ask anyone to explain the reason for this vilification and most will blame the yakuza and their penchant for body ink; better-informed citizens may even trace the roots of negative attitudes to the 17th century when criminals were tattooed as a form of punishment.

However, such explanations for Japan’s longstanding animosity toward tattoos are, at best, an oversimplification — and, at worst, most incorrect.

Instead of targeting wrongdoers, Japanese prohibitions against tattoos have historically been aimed at the working classes, women, and ethnic minorities, and today the bearer of a full-back tattoo is increasingly likely to be a sensitive salaryman rather than a punch-permed thug or criminal.

Japan has had a long tattoo history.

The history of body modification in Japan is long and vibrant, dating back to the Jomon Period (roughly 10,500 B.C. to 300 B.C.) when clay figurines were molded with marks that modern historians interpret as either tattoos or scarification.

There isn't any physical proof that the Jomon people tattooed themselves; however, a Chinese historical record written at around 300 A.D. said all Japanese men tattooed their faces and bodies.

This history is marked by a love-hate relationship: In the 17th century, for example, criminals were tattooed to blatantly mark them in shame instead of punishment through mutilation.

Edo Period

The end of the Edo Period (1603-1868) was the golden age of tattooing. During this time, Japan was a military dictatorship governed by a corrupt samurai elite who had barricaded the country from the outside world and imposed a strict social hierarchy on the population.

The end of the Edo Period (1603-1868) was the golden age of tattooing. During this time, Japan was a military dictatorship governed by a corrupt samurai elite who had barricaded the country from the outside world and imposed a strict social hierarchy on the population.

Punishment and tattoos

some criminals even had the Japanese for "dog" (犬) inked on their foreheads. During the following century, however, tattoos became fashionable.

some criminals even had the Japanese for "dog" (犬) inked on their foreheads. During the following century, however, tattoos became fashionable.

However, tattoos were banned in the mid-to-late 19th century as the country opened up to the outside world.

And this stigma isn't a recent phenomenon or going away anytime soon.

Stigma

The fear was that the custom might seem primitive to foreigners or mocked abroad. The Japanese government saw tattoos as "barbaric" and certainly not part of their program to modernize.

It wasn't until after World War II that the legal prohibition against tattooing was lifted. By then, the stigma had once again set in.

But not everyone who has tattoos in Japan is in organized crime. Regular people also have them.. Celebrities, too.

Some Japanese have them for the same reasons that people do in the West, whether that's fashion or simply because they are interested in body art.

However, tattoos are far more of a rarity in daily life in Japan than abroad.

Prejudice against tattoos

For many Japanese people, though, the association of tattoos to thuggery is stronger than ever; bans on ink at swimming pools, hot springs, and even some beaches are increasingly widespread.

These misguided regulations often inflict collateral damage.

In 2015, for example, a Maori woman from New Zealand with a traditional facial tattoo was refused entry to a hot spring in Hokkaido — the owners seemingly ignorant of their own island’s long history of female tattooing. Despite such discrimination, increasing numbers of Japanese people are going under the needle.

Today there are an estimated 3,000 tattoo artists working in Japan, compared to approximately 200 in the 1990’s.

As of yet, Japanese people’s tattoos remain largely out of sight.

However, a day may come soon when a great wave of ink washes aside outdated discrimination and people can embrace again one of their oldest — and most persistent — forms of art.

Writers Note -

If you have tattoos and are planning on visiting Japan, you might run into problems at, for example, hot springs and public pools.

Either cover your tattoos with bandages or band-aids (if possible!) or rent rooms at hot springs that come with a private bath.

For business trips, unless your work is connected to the arts, it might be a good idea to discretely cover your ink (if at all possible)