Few Japanese sweets are as closely tied to the rhythm of the seasons as Ohagi (おはぎ).

This traditional rice sweet is most often enjoyed during Higan — a Buddhist celebration that takes place twice a year, around the spring and autumn equinox.

Soft, sweet, and beautifully simple, Ohagi has long been a comfort food that connects generations and reminds people of family and home.

Ohagi or Botamochi?

Depending on the season or region, Ohagi is sometimes called Botamochi (ぼたもち).

Traditionally, sweets made during spring were called Botamochi — named after the botan (peony) flower — while those made in autumn were called Ohagi, inspired by the hagi (bush clover).

In practice, both names refer to the same treat: a ball of soft, half-pounded sticky rice covered with anko, sweet red bean paste.

made with sweet red bean paste (anko), a staple in many Japanese desserts.

The difference in names beautifully reflects Japan’s deep appreciation for the changing seasons — a theme found throughout Japanese culture.

How It’s Made

Ohagi begins with glutinous rice (mochi-gome) steamed and then gently pounded until it’s slightly sticky but still retains some grain texture.

The rice is shaped into small ovals, roughly the size of a child’s fist, and coated with sweet bean paste — smooth or slightly coarse, depending on taste.

Different Types of Ohagi

Anko Ohagi

The most classic version is covered with anko. Smooth red bean paste creates a soft, refined texture, while coarse anko offers a more rustic taste.

Both pair beautifully with a cup of green tea, balancing sweetness with gentle bitterness.

Kinako Ohagi

Another popular variety is coated with kinako — roasted soybean flour.

Kinako Ohagi has a mellow, nutty flavor and a warm golden color that contrasts beautifully with the deep red of anko-covered ones.

It’s often enjoyed by those who prefer a lighter, less sweet taste.

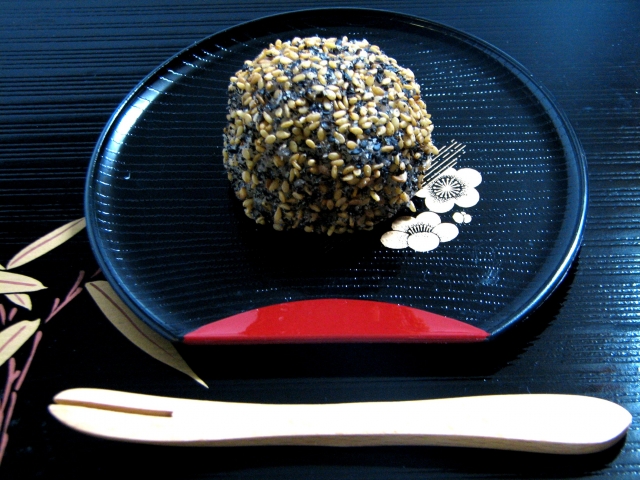

Goma Ohagi

For a bolder flavor, goma (ground sesame) Ohagi is a favorite.

Coated with black or white sesame powder mixed with a hint of sugar, this type offers a toasty aroma and visually striking look on the dessert plate.

A Family Tradition

During both spring and autumn Higan, many families prepare Ohagi at home.

Mothers and grandmothers often make large batches in traditional juubako boxes to share with neighbors and relatives — a gesture of connection and gratitude.

For many Japanese, the taste of homemade Ohagi is a flavor of nostalgia, evoking memories of family gatherings and seasonal celebrations.

A Sweet Expression in Everyday Life

Ohagi even has a famous idiom in Japanese.

When an unexpected stroke of luck comes your way, people say:

“棚からぼたもち (Tana kara Botamochi)” — “a Botamochi falls from the shelf.”

It’s used to describe good fortune that comes effortlessly — like a delicious surprise.

More Than a Sweet

Beyond its taste, Ohagi represents something deeper — Japan’s mindfulness toward the seasons, gratitude toward nature, and the comfort of sharing food with others.

Whether enjoyed at a temple, a family table, or a small tea gathering, Ohagi continues to embody the simple joy of life’s changing seasons.

Related Articles

Sekihan: The Red Rice Served on Happy Occasions — Discover why this celebratory dish represents joy and gratitude in Japanese culture.

Japanese Tea Culture: The Heart of Everyday Calm — Explore how tea and sweets like Ohagi create perfect harmony in Japanese life.

Japanese Festivals: The Energy and Spirit of Celebration — Learn how traditional sweets and festivals reflect the joy of each season.